I think few would argue that the online safety risks which students are exposed to these days have gone down. But the big question is, has the effort of schools in protecting students changed in step with increased risk exposure?

But first some good news

Before I go any further, I need to be clear here that this post looks very much at the negative side of things in relation to online safety however in doing so I run the risk of painting a purely negative picture. I therefore think its important to point out the positives of technology. Communication, collaboration, friendship and many more areas of life can see a benefit from appropriate use of online technologies. An Ofcom 2022 report identified that 80% of the children surveyed used online services to find support for the wellbeing, that 53% felt being online was good for their mental health and that 69% of children thought being online helped then feel close to their friends and peers. It is important that we appreciate these positives as for me this highlights the focus should not be about blocking and filtering, which is increasing ineffective, but about discussion and engagement of students around risks and behaviours.

New Apps and Technologies

And now for the risks; I would suggest most students now have mobile phones with internet access, with access to apps such as snapchat, Instagram and the very popular TikTok. The Ofcom survey found that 90% of children owned a mobile phone by the time they reached the age of 11. This access to technology and every changing and evolving app space represents a risk in the explosion of inappropriate content and contacts which students can access via the device in their pockets. As adults and educators we cannot truly know the implications, and this is important to acknowledge, as the situation when we were children was significantly different. There is also a risk here in relation to the increasing use of AI or machine learning within apps to feed users with the content they appear interested in, reinforcing these interests or curiosities even when exposure to such content may be inappropriate or even dangerous.

Pandemic

The pandemic accelerated things pushing everyone more online than ever before as we had to learn through online contact with teachers, maintain relationships with friends and families again through online solutions and occupy our time without leaving our homes, an issue which online games and other platforms where all too happy to address. It wasn’t so much a case of “should we” engage with technology, online tools and online spaces, but a case of what other choice do we have. This has both increased the need to use and also the use of technology, including all its benefits but also risks.

IT Curriculum

We have also seen a decrease in time in schools where digital citizenship, its risks and issues can be discussed. Yes online safety should appear across the curriculum and as part of keeping children safe in education, however there are lots of other competing topics and requirements. Previously the GCSE IT provided an opportunity for specific time to be allocated to discussions of digital citizenship and online safety however with its removal this opportunity has been lost. Now some may say the Computer Science GCSE is still available, however it doesn’t have the same number of students studying for it plus as a subject has a decidedly different slant than the old GCSE IT, which doesn’t lend itself to quite as much discussion of digital citizenship. Now I will note the GCSE IT wasn’t without its problems as a course, however I feel a redesign would have helped rather than its removal. Looking forward, I see similar risk of lost opportunity in the planned defunding of the BTec qualifications which include a number of IT qualifications.

Conclusions

I think all schools will likely be able to point to what they do in relation to online safety. My concern though is this hasn’t changed much over the years. Celebration of internet safety day, annual talks or presentations, digital councils and/or digital leaders meetings involving students, etc, these are not new, yet the risks and exposure of our students to technology and these risks has grown significantly, and even more so over the last two or three years, driven by the pandemic. The risks are growing yet the mitigation measures largely remain the same. There is a clear inbalance.

I think one of the biggest challenges continues to be time. The curriculum is already full of content and various competing requirements, with most offering value. The question therefore is one of identifying where there is the greatest value and I would advocate that time allocated to digital citizenship is critical. The challenge here is I don’t feel education is particularly good at this prioritisation, instead trying to do everything, and in doing so this causes workload issues, greatly subdivided focus and other issues.

Technology use is only going to increase so the more we can prepare our students, and get them to evaluate and consider how, when and where they use technology, the better. Digital citizenship needs to occupy a bigger part of student studies, both in preparing them for the future, but also equipping them to deal with technology risks both now and in the future.

Before the Covd-19 crisis begun I presented on Digital Citizenship at the JISC DigiFest event and previous to that at the ISC Digital event in Brighton. In both cases one of my reasons for presenting was my concern regarding students increasing use of technology not being match by an appropriate considerations or awareness of the risks. I was worried that students were giving away large amounts of data without considering who they were providing to, how it might be used, how long it would be kept or how it might impact or be used to influence them as individuals, and as groups, in their future. I was worried and believed education and its educators needed to start to do something about this.

Before the Covd-19 crisis begun I presented on Digital Citizenship at the JISC DigiFest event and previous to that at the ISC Digital event in Brighton. In both cases one of my reasons for presenting was my concern regarding students increasing use of technology not being match by an appropriate considerations or awareness of the risks. I was worried that students were giving away large amounts of data without considering who they were providing to, how it might be used, how long it would be kept or how it might impact or be used to influence them as individuals, and as groups, in their future. I was worried and believed education and its educators needed to start to do something about this. It is important to firstly acknowledge that our views on technology are very much the result of our experiences. My experiences include learning to code in Basic on the Commodore 64 at an early age, before moving on to AMOS basic on the Amiga and then QBasic, Visual Basic and C++ on the PC. This early use of technology, and the ability to develop software to solve problems has very much shaped my views. Now, today I walk around with a mobile phone with over a million times more memory than my commodore 64, from less than 30 years earlier, and the growth rate across the period has not been linear. A perfect illustration of this lies in how long it took various technologies to reach 50 million users. Radio took 75 years whereas TV only took 38 years. Bringing us close to today, Facebook got the time to 50 million users down to 3.5 years before Pokemon go managed it in less than a single month. It is clear from this that the pace of changing is quickening.

It is important to firstly acknowledge that our views on technology are very much the result of our experiences. My experiences include learning to code in Basic on the Commodore 64 at an early age, before moving on to AMOS basic on the Amiga and then QBasic, Visual Basic and C++ on the PC. This early use of technology, and the ability to develop software to solve problems has very much shaped my views. Now, today I walk around with a mobile phone with over a million times more memory than my commodore 64, from less than 30 years earlier, and the growth rate across the period has not been linear. A perfect illustration of this lies in how long it took various technologies to reach 50 million users. Radio took 75 years whereas TV only took 38 years. Bringing us close to today, Facebook got the time to 50 million users down to 3.5 years before Pokemon go managed it in less than a single month. It is clear from this that the pace of changing is quickening. The more I think about the pace of change and the way that technology is becoming an integral part of our everyday lives the more the movie Ready Player One comes to mind. In the movie Wade Watts makes use of virtual reality to live a double life, living as Percival in VR. As the film progresses it becomes clear that his two lives aren’t as separate as he would like and that events in virtual reality impact on real life and vice versa. For us, like Wade Watts, our lives in real life are inseparably linked to our digital lives. In fact, I believe that it no longer serves us to think of digital citizenship as the term implies that there is something else available, a non-digital citizenship, when in fact there is not. Possibly the discussion should not be of digital citizenship at all but simply citizenship. As Danah Boyd, in her book, Its Complicated said, although the apps might change our online connectedness, our need to share and the challenges around privacy are “here to stay”.

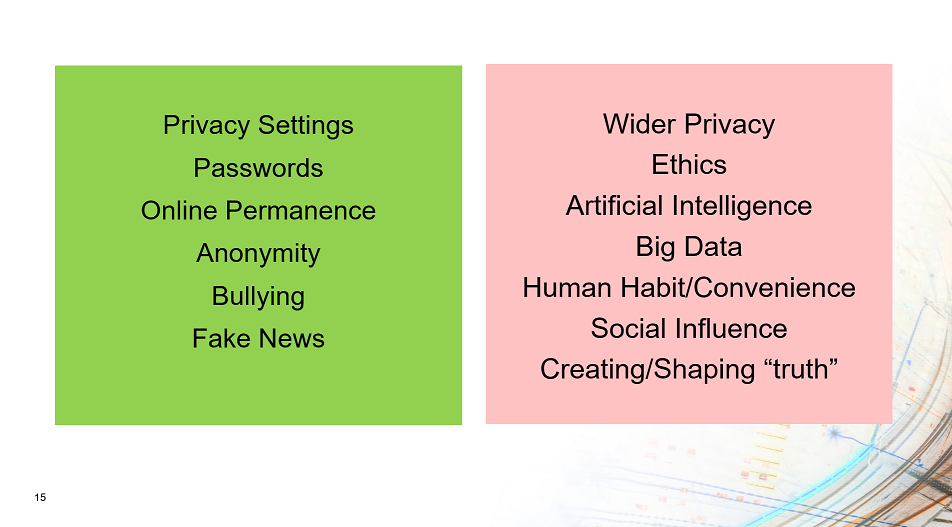

The more I think about the pace of change and the way that technology is becoming an integral part of our everyday lives the more the movie Ready Player One comes to mind. In the movie Wade Watts makes use of virtual reality to live a double life, living as Percival in VR. As the film progresses it becomes clear that his two lives aren’t as separate as he would like and that events in virtual reality impact on real life and vice versa. For us, like Wade Watts, our lives in real life are inseparably linked to our digital lives. In fact, I believe that it no longer serves us to think of digital citizenship as the term implies that there is something else available, a non-digital citizenship, when in fact there is not. Possibly the discussion should not be of digital citizenship at all but simply citizenship. As Danah Boyd, in her book, Its Complicated said, although the apps might change our online connectedness, our need to share and the challenges around privacy are “here to stay”. Looking at how we prepare our students for the world and the issues listed above I can see the things which we do satisfactorily, through our eSafety programmers, however I can also see those areas where little or nothing is currently offered. We currently discuss the importance of privacy settings on social media, of having strong passwords, of how online content, once posted, will remain permanent and of the need to be aware of bullying online. These areas are currently covered. Sadly, however little is said in relation to the conflict between user convenience and individual privacy, between individual privacy and public good, and between social media reporting on or actually creating the news and truths which we come to believe. These are the areas which we need to discuss, for which there isn’t a single answer and therefore where the most we can do is help students develop their own views through discussion. It is through discussion that we can hopefully ensure that students, when presented with the infinite challenges of technology use, will approach them with their eyes wide open.

Looking at how we prepare our students for the world and the issues listed above I can see the things which we do satisfactorily, through our eSafety programmers, however I can also see those areas where little or nothing is currently offered. We currently discuss the importance of privacy settings on social media, of having strong passwords, of how online content, once posted, will remain permanent and of the need to be aware of bullying online. These areas are currently covered. Sadly, however little is said in relation to the conflict between user convenience and individual privacy, between individual privacy and public good, and between social media reporting on or actually creating the news and truths which we come to believe. These are the areas which we need to discuss, for which there isn’t a single answer and therefore where the most we can do is help students develop their own views through discussion. It is through discussion that we can hopefully ensure that students, when presented with the infinite challenges of technology use, will approach them with their eyes wide open. I thought I would share some initial thoughts following day one of JISC DigiFest. The event was launched with a very polished and professional pre-prepared video displayed on screens scattered around the events main hall, focussing on the rate of change in relation to technology and some of the technological implications of technology on the world we live in. The launch session also included a room height “virtual” event guide introducing the sessions and pointing you in the direction of the appropriate hall. In terms of the launch of a conference this was the most polished and inspiring launch I have seen albeit on reflection there wasn’t much particularly innovative or technically complex about it.

I thought I would share some initial thoughts following day one of JISC DigiFest. The event was launched with a very polished and professional pre-prepared video displayed on screens scattered around the events main hall, focussing on the rate of change in relation to technology and some of the technological implications of technology on the world we live in. The launch session also included a room height “virtual” event guide introducing the sessions and pointing you in the direction of the appropriate hall. In terms of the launch of a conference this was the most polished and inspiring launch I have seen albeit on reflection there wasn’t much particularly innovative or technically complex about it. The keynote speaker addressed the changing viewpoints of different generations of people focussing particularly on Generation Z, the generation which currently are in our sixth forms, colleges and universities. I took away two key points from the presentation. The first was how each generations views were shaped by their experiences particularly between the ages of 12 and 20 year old. Jonah Stillman used thoughts on space as an example showing how Generation X might have positive views focussing on the successes of the moon landing whereas Millennials may have a more cynical view following the Challenger disaster. Additionally, Jonah mentioned movies as a social influencer and how those in the Harry Potter generation may view cooperation and trying hard, even where unsuccessful, in a positive manner. Those born later than this may draw on another series of films, in the hunger games, resulting in a greater tendency towards competition and the need to succeed in line with the movies storyline of everyone for themselves and failure results in death. The second take away point from the session resulted from the questioning at the end of the session around what some saw as the absoluteness of the boundaries between generations. I think Jonah’s use of the word “tendency” addressed this concern in that the purpose of the labels was for simplicity and to indicate a general trend and tendency rather than to suggest that all people born on certain dates exhibited a certain trait. It increasing concerns me that this argument keeps coming up when surely it is clear that there is a need to use simplistic models to help clarity of explanation and that no model, not matter how complex will ever truly capture the real complexity of the world we live in.

The keynote speaker addressed the changing viewpoints of different generations of people focussing particularly on Generation Z, the generation which currently are in our sixth forms, colleges and universities. I took away two key points from the presentation. The first was how each generations views were shaped by their experiences particularly between the ages of 12 and 20 year old. Jonah Stillman used thoughts on space as an example showing how Generation X might have positive views focussing on the successes of the moon landing whereas Millennials may have a more cynical view following the Challenger disaster. Additionally, Jonah mentioned movies as a social influencer and how those in the Harry Potter generation may view cooperation and trying hard, even where unsuccessful, in a positive manner. Those born later than this may draw on another series of films, in the hunger games, resulting in a greater tendency towards competition and the need to succeed in line with the movies storyline of everyone for themselves and failure results in death. The second take away point from the session resulted from the questioning at the end of the session around what some saw as the absoluteness of the boundaries between generations. I think Jonah’s use of the word “tendency” addressed this concern in that the purpose of the labels was for simplicity and to indicate a general trend and tendency rather than to suggest that all people born on certain dates exhibited a certain trait. It increasing concerns me that this argument keeps coming up when surely it is clear that there is a need to use simplistic models to help clarity of explanation and that no model, not matter how complex will ever truly capture the real complexity of the world we live in.

I had the opportunity to present at the Brighton ISC Digital EdTech summit during the week. My talk, “Common Sense Safeguarding” focussed on the need for schools to take a broad and more risk based view of online safety as opposed to the previous more compliance driven approach. Given the number and range of technologies students have access to and also the tools available to bypass protective measures put in place by a school, or even the ability to negate them totally through using 4G, online safety is no longer as simple as it once was. This therefore needs a broader view to be taken.

I had the opportunity to present at the Brighton ISC Digital EdTech summit during the week. My talk, “Common Sense Safeguarding” focussed on the need for schools to take a broad and more risk based view of online safety as opposed to the previous more compliance driven approach. Given the number and range of technologies students have access to and also the tools available to bypass protective measures put in place by a school, or even the ability to negate them totally through using 4G, online safety is no longer as simple as it once was. This therefore needs a broader view to be taken.